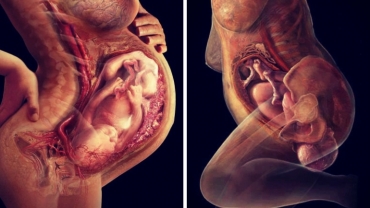

Forceps are a surgical instrument that resembles a pair of tongs and can be used in surgery for grabbing, maneuvering, or removing various things within or from the body. They're curved to fit around the baby's head. The forceps are carefully positioned around your baby's head and joined together at the handles. With a contraction and your pushing, an obstetrician gently pulls to help deliver your baby.

There are many different types of forceps. All American forceps are derived from French forceps (long forceps) or English forceps (short forceps). Short forceps are applied on the fetal head already descended significantly in the maternal pelvis (i.e., proximal to the vagina). Long forceps are able to reach a fetal head still in the middle or even in the upper part of the maternal pelvis. At present practice, it is uncommon to use forceps to access a fetal head in the upper pelvis. So, short forceps are preferred in UK and USA. Long forceps are still in use elsewhere.

Simpson forceps (1848) are the most commonly used among the types of forceps and has an elongated cephalic curve. These are used when there is substantial molding, that is, temporary elongation of the fetal head as it moves through the birth canal.

Elliot forceps (1860) are similar to Simpson forceps but with an adjustable pin in the end of the handles which can be drawn out as a means of regulating the lateral pressure on the handles when the instrument is positioned for use. They are used most often with women who have had at least one previous vaginal delivery because the muscles and ligaments of the birth canal provide less resistance during second and subsequent deliveries. In these cases the fetal head may thus remain rounder.

Kielland forceps (1915, Norwegian) are distinguished by having no angle between the shanks and the blades and a sliding lock. The pelvic curve of the blades is identical to all other forceps. The common misperception that there is no pelvic curve has become so entrenched in the obstetric literature that it may never be able to be overcome, but it can be proved by holding a blade of Kielland's against any other forceps of one's choice. Probably the most common forceps used for rotation. The sliding mechanism at the articulation can be helpful in asyncletic births (when the fetal head is tilted to the side), since the fetal head is no longer in line with the birth canal. Because the handles, shanks and blades are all in the same plane the forceps can be applied in any position to effect rotation. Because the shanks and handles are not angled the forceps cannot be applied to a high station as readily as those with the angle since the shanks impinge on the perineum.

Wrigley's forceps are used in low or outlet delivery (see explanations below), when the maximum diameter is about 2.5 cm above the vulva.[5] Wrigley's forceps were designed for use by general practitioner obstetricians, having the safety feature of an inability to reach high into the pelvis. Obstetricians now use these forceps most commonly in cesarean section delivery where manual traction is proving difficult. The short length results in a lower chance of uterine rupture.

Piper's forceps have a perineal curve to allow application to the after-coming head in breech delivery.

What are the risks of a ventouse or forceps birth?

Ventouse and forceps are safe ways to deliver a baby, but there are some risks that should be discussed with you. Your obstetrician or midwife should also discuss the reasons for having an assisted birth, the choice of instrument (forceps or ventouse), and the procedure for carrying out an assisted birth. The risks are listed here.

- Vaginal tearing or episiotomy

- Third- or fourth-degree vaginal tear

- Higher risk of blood clots

- Urinary incontinence

- Anal incontinence

- 1962 views